Britain Arrests WikiLeaks Founder on Sex Charges

By ALAN COWELL and SCOTT SHANE

Published: December 7, 2010

LONDON — British police said on Tuesday they had arrested Julian Assange, the beleaguered founder of the WikiLeaks anti-secrecy group, on a warrant issued in Sweden in connection with alleged sex offenses.

Mr. Assange, a 39-year-old Australian, was arrested by officers from Scotland Yard’s extradition unit when he went to a central London police station by prior agreement with the authorities, the police said. A court hearing was expected later.

A Metropolitan Police spokesman, quoted by Britain’s Press Association news agency, said: “Officers from the Metropolitan Police extradition unit have this morning arrested Julian Assange on behalf of the Swedish authorities on suspicion of rape.”

The widely anticipated arrest came after Mr. Assange, who denies the charges of sexual misconduct said to have been committed while he was in Sweden in August, threatened to release many more diplomatic cables if legal action is taken against him or his organization.

Mr. Assange’s threat of further disclosures poses a problem for the Obama administration as it explores ways to prosecute Mr. Assange or the group in relation to the archive of some 250,000 diplomatic cables it has obtained, reportedly from a low-ranking Army intelligence analyst.

A police spokesman said Mr. Assange was “accused by the Swedish authorities of one count of unlawful coercion, two counts of sexual molestation and one count of rape, all alleged to have been committed in August 2010.”

Mark Stephens, Mr. Assange’s British lawyer, confirmed late Monday in a video statement to the BBC that the authorities in London had “received an extradition request from Sweden,” and he said that he and Mr. Assange were “in the process of making arrangements to meet with the police by consent.”

The charges involve sexual encounters that two women say began as consensual but became nonconsensual after Mr. Assange was no longer using a condom. Mr. Assange has denied any wrongdoing and suggested that the charges were trumped up in retaliation for his WikiLeaks work, though there is no public evidence to suggest a connection.

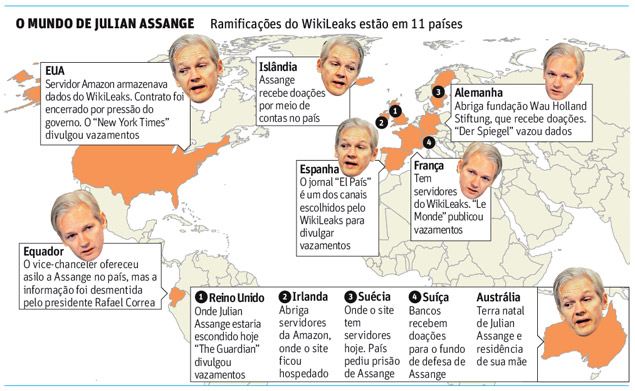

Mr. Assange’s arrest came amid growing challenges to his operations, as computer server companies, Amazon.com and PayPal.com, have cut off commercial cooperation with WikiLeaks.

On Monday, a Swiss bank froze an account held by Mr. Assange that had been used to collect donations for WikiLeaks. Marc Andrey, a spokesman for the bank, PostFinance, an arm of the Swiss postal service, said the account was closed because Mr. Assange “gave us false information when he opened the account,” asserting inaccurately that he lived in Switzerland.

In the United States on Monday, moreover, Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. said the Justice Department had “a very serious, active, ongoing investigation that is criminal in nature” into the WikiLeaks matter.

“I authorized just last week a number of things to be done so that we can hopefully get to the bottom of this and hold people accountable,” he said at a news conference, declining to elaborate.

Mr. Holder’s statement followed Mr. Assange’s assertion that “over 100,000 people” had been given the entire archive of 251,287 cables “in encrypted form.”

“If something happens to us, the key parts will be released automatically,” Mr. Assange said Friday in a question-and-answer session on the Web site of the British newspaper The Guardian.

His threat is not idle, because as of Monday night the group had released fewer than 1,000 of the quarter-million State Department cables it had obtained, reportedly from a low-ranking Army intelligence analyst.

So far, the group has moved cautiously. The whole archive was made available to five news organizations, including The New York Times. But WikiLeaks has posted only a few dozen cables on its own in addition to matching those made public by the news publications. According to the State Department’s count, 1,325 cables, or fewer than 1 percent of the total, have been made public by all parties to date.

There appears to be no way for American authorities to retrieve all copies of the cables archive. And legal experts say there are serious obstacles to any prosecution of Mr. Assange or his group.

But the disclosure of the confidential communications between the State Department and 270 American embassies and consulates has infuriated administration officials and prompted calls from Congress to pursue charges.

Mr. Holder repeated assertions by several Obama administration officials about the damage done by the cable disclosures, which began late last month.

“The national security of the United States has been put at risk; the lives of people who work for the American people have been put at risk; the American people themselves have been put at risk by these actions that are, I believe, arrogant, misguided and ultimately not helpful in any way,” Mr. Holder said.

Justice Department prosecutors have been struggling to find a way to indict Mr. Assange since July, when WikiLeaks made public documents on the war in Afghanistan. But while it is clearly illegal for a government official with a security clearance to give a classified document to WikiLeaks, it is far from clear that it is illegal for the organization to make it public.

The Justice Department has considered trying to indict Mr. Assange under the Espionage Act, which has never been successfully used to prosecute a third-party recipient of a leak. Some lawmakers have suggested accusing WikiLeaks of receiving stolen government property, but experts said Monday that would also pose difficulties.

Perhaps in a warning shot of sorts, WikiLeaks on Monday released a cable from early last year listing sites around the world — from hydroelectric dams in Canada to vaccine factories in Denmark — that are considered crucial to American national security.

Nearly all the facilities listed in the document, including undersea cables, oil pipelines and power plants, could be identified by Internet searches. But the disclosure prompted headlines in Europe and a new denunciation from the State Department, which said in a statement that “releasing such information amounts to giving a targeting list to groups like Al Qaeda.”

Asked later about the cable, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton said the continuing disclosures posed “real concerns, and even potential damage to our friends and partners around the world.”

“I won’t comment on any specific alleged cable, but I will underscore that this theft of U.S. government information and its publication without regard to the consequences is deeply distressing,” she said.

In recent months, WikiLeaks gave the entire collection of cables to four European publications — Der Spiegel in Germany, El País in Spain, Le Monde in France and The Guardian. The Guardian shared the cable collection with The New York Times.

Since Nov. 28, each publication has been publishing a series of articles about revelations in the cables, accompanied online by the texts of some of the documents. The publications have removed the names of some confidential sources of American diplomats, and WikiLeaks has generally posted the cables with the same redactions.

But with the initial series of articles and cable postings nearing an end, the fate of the roughly 250,000 cables that have not been placed online is uncertain. The five publications have announced no plans to make public all the documents. WikiLeaks’s intentions remain unclear.

There appears to be no way for American authorities to retrieve all copies of the cables archive. And legal experts say there are serious obstacles to any prosecution of Mr. Assange or his group.

But the disclosure of the confidential communications between the State Department and 270 American embassies and consulates has infuriated administration officials and prompted calls from Congress to pursue charges.

Mr. Holder repeated assertions by several Obama administration officials about the damage done by the cable disclosures, which began late last month.

“The national security of the United States has been put at risk; the lives of people who work for the American people have been put at risk; the American people themselves have been put at risk by these actions that are, I believe, arrogant, misguided and ultimately not helpful in any way,” Mr. Holder said.

Justice Department prosecutors have been struggling to find a way to indict Mr. Assange since July, when WikiLeaks made public documents on the war in Afghanistan. But while it is clearly illegal for a government official with a security clearance to give a classified document to WikiLeaks, it is far from clear that it is illegal for the organization to make it public.

The Justice Department has considered trying to indict Mr. Assange under the Espionage Act, which has never been successfully used to prosecute a third-party recipient of a leak. Some lawmakers have suggested accusing WikiLeaks of receiving stolen government property, but experts said Monday that would also pose difficulties.

Perhaps in a warning shot of sorts, WikiLeaks on Monday released a cable from early last year listing sites around the world — from hydroelectric dams in Canada to vaccine factories in Denmark — that are considered crucial to American national security.

Nearly all the facilities listed in the document, including undersea cables, oil pipelines and power plants, could be identified by Internet searches. But the disclosure prompted headlines in Europe and a new denunciation from the State Department, which said in a statement that “releasing such information amounts to giving a targeting list to groups like Al Qaeda.”

Asked later about the cable, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton said the continuing disclosures posed “real concerns, and even potential damage to our friends and partners around the world.”

“I won’t comment on any specific alleged cable, but I will underscore that this theft of U.S. government information and its publication without regard to the consequences is deeply distressing,” she said.

In recent months, WikiLeaks gave the entire collection of cables to four European publications — Der Spiegel in Germany, El País in Spain, Le Monde in France and The Guardian. The Guardian shared the cable collection with The New York Times.

Since Nov. 28, each publication has been publishing a series of articles about revelations in the cables, accompanied online by the texts of some of the documents. The publications have removed the names of some confidential sources of American diplomats, and WikiLeaks has generally posted the cables with the same redactions.

But with the initial series of articles and cable postings nearing an end, the fate of the roughly 250,000 cables that have not been placed online is uncertain. The five publications have announced no plans to make public all the documents. WikiLeaks’s intentions remain unclear.