1954 Guatemalan coup d'état

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

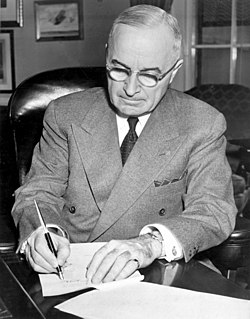

The 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état (18–27 June 1954) was the CIA covert operation that deposed President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, with Operation PBSUCCESS — paramilitary invasion by an anti-Communist “army of liberation”. In the early 1950s, the politically liberal Árbenz Government had effected the socio-economics of Decree 900 (27 June 1952), such as the expropriation,

for peasant use and ownership, of unused prime-farmlands that national

and multinational corporations had earlier set aside, as reserved

business assets. The land-reform of Decree 900 especially threatened the

agricultural monopoly of the United Fruit Company, the multinational corporation that owned 42 per cent of the arable land of Guatemala; which landholdings either had been bought by, or been ceded to, the UFC by the military dictatorships

who preceded the Árbenz Government of Guatemala. In response to the

expropriation of prime-farmland assets, the United Fruit Company asked

the U.S. governments of presidents Harry Truman (1945–53) and Dwight

Eisenhower (1953–61) to act diplomatically, economically, and militarily

against Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán.[1] The thirty-six-year Guatemalan Civil War, which began on 13 November 1960, resulted in the deaths of 140,000 to 250,000 Guatemalans.

Initially, the U.S. perceived no political or economic threat from

the election of President Árbenz Guzmán, because he appeared to have “no

real sympathy for the lower classes”, but, shortly after he was elected

President, he continued the program of the Arévalo Government, which,

although “favorably disposed, initially, toward the United States, was

modeled in many ways after the Roosevelt New Deal”;

yet, such relative political and economic liberalism in a Latin

American country was worrisome to American corporate and political

interests.[2][3]

The Inter-American Affairs Bureau officer Charles R. Burrows, of the

U.S. State Department, explained the perceived threat to U.S. interests:

“Guatemala has become an increasing threat to the stability of Honduras

and El Salvador. Its agrarian reform is a powerful propaganda weapon;

its broad social program, of aiding the workers and peasants in a

victorious struggle against the upper classes and large foreign

enterprises, has a strong appeal to the populations of Central American

neighbors, where similar conditions prevail”. Because Central America

was a small area, with porous national borders, political news travelled

quickly, and “it was impossible to escape the contagion”, said the

right-wing journalist Clemente Marroquín Rojas when the May 1954 general

strike paralyzed the north coast of Honduras. Moreover, from El Salvador, President Óscar Osorio (1950–56) sent a message of fear, and warned that his country “would be next on the list.”[4][5]

In the geopolitical context of the U.S.–U.S.S.R. Cold War (1945–1991), the secret intelligence agencies of the U.S. deemed such liberal land-reform nationalization as government communism, instigated by the U.S.S.R. The intelligence analyses led CIA director Allen Dulles to fear that the Republic of Guatemala would become a “Soviet beachhead in the Western Hemisphere”, the “back yard” of U.S. hegemony.[6] Moreover, in the context of the aggressive anti-Communism of the McCarthy era (1947–57), CIA Director Allen Dulles, the American people, the CIA, and the Eisenhower Administration (1953–61) shared the same fear — Soviet infiltration of the Western Hemisphere. Moreover, like his brother, John Foster Dulles, the U.S. Secretary of State, CIA Director Allen Dulles owned capital stock

in the United Fruit Company, which conflict of interest they conflated

to the Western-hemisphere geopolitics of the United States, the secret

invasion of Guatemala, to change its national government.[7] (See: The Monroe Doctrine.)

The Guatemalan coup d'état began with Operation PBFORTUNE (September 1952), the partly implemented plan to supply exiled, right-wing, anti–Árbenz rebel groups with operational funds and matériel, to form a counter-revolutionary

“army of liberation” to depose the Árbenz Government. The Guatemalan

paramilitary invasion was contingent upon U.S. intelligence confirmation

that President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán was a Communist. Two years later,

in June 1954, Operation PBSUCCESS realised the coup d'état, and installed Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas as President of Guatemala. Afterwards followed Operation PBHISTORY

(July 1954), with the intelligence-gathering remit to find and publish

evidence (government and communist-party documents) to try to confirm

the geopolitical analysis of the CIA: that under the Árbenz Government,

Guatemala was a pro-Communist puppet state of the U.S.S.R. — a part of the Soviet hegemony in the Western Hemisphere.[8] However, the CIA document-analysis team of Operation PBHISTORY found no government or communist (Guatemalan Labour Party) document that supported the American ideologic assumption that the Árbenz Government had been infiltrated

by Soviet-controlled, Guatemalan Communists. Moreover, the PBHISTORY

intelligence analyses of the Árbenz Government documents indicated that

President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán had abided Guatemalan constitutional law,

by respecting the right of national Communists to form political

parties and to participate in national politics, in the senate of the

Republic of Guatemala; and that Guatemalan Communists were nationalists,

ideologically independent of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

The paramilitary invasion, Operation PBSUCCESS (1953–54) featured El ejército de liberación — an “army of liberation” recruited, trained, and armed by the CIA, composed of 480 mercenary soldiers under the command of Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, an exiled Guatemalan army officer. The CIA army for the liberation of Guatemala was part of a complex of diplomatic, economic, and propaganda campaigns. To disseminate the propaganda and the disinformation (black propaganda) that the Árbenz Government were Communists, the CIA established Voz de la liberación

(Voice of Liberation, VOL), a radio station to transmit from Miami,

Florida, USA, whilst claiming to be in the Guatemalan jungle with the liberacionista

army of Col. Castillo Armas. The liberationist propaganda and

disinformation misrepresented the VOL as the spontaneous voice of

domestic, counter-revolutionary Guatemalan patriots who opposed the

Communism of the elected Árbenz Government.

The compelled resignation of the Presidency of Guatemala, by Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, ended the liberal, political experimentation of the “Ten Years of Spring”, which had begun with the October Revolution of 1944, which established representative democracy in Guatemala.[9] In 1957, three years after the Guatemalan coup d'état,

Col. Castillo Armas was assassinated, and replaced by another military

government; in 1960, three years later, began the 36-year Guatemalan Civil War (1960–96), featuring brutal counterinsurgency operations and massacres, which conflated historical ethnic conflict between ladino (mestizo) Guatemalans and ethnic Maya Guatemalans, who were accused of being either communists or communist sympathizers. In the post–civil war period, the Guatemalan Historical Clarification Commission classified such counterinsurgency killings of the Guatemalan civil populace as genocide.

Contents |

Historical background

- The Monroe Doctrine

In the 1890s, the U.S. enforced the Monroe Doctrine (1823), and replaced European colonial Imperialism in the Americas with the hegemony

of the U.S. upon the natural resources, and the labor of the peoples of

the Latin American countries, and the island countries in the Caribbean

sea. In Central America, in Guatemala, the military dictators

who ruled the country during the late 19th and the early 20th centuries

readily accommodated the financial interests of American multinational corporations,

and the ideological interests of the U.S. Government. Unlike military

occupation, involving the direct imperial control of the politics and

the economies of countries such as Haiti, Nicaragua, and Cuba,

in Guatemala, the U.S. exerted indirect, hegemonic control of the

country, by means of either a sponsored government, or an installed

government. The political subordinations of the country and the nation

were achieved with the close co-operation of the Guatemalan Army and the

civil police forces with their counterpart U.S. military and civil

police forces; jointly, they maintained national law and order, which

secured the corporate financial interests of U.S. businesses in

Guatemala. Moreover, the dictators also exempted some U.S. corporations

from paying taxes to the Guatemalan national treasury; sold the public utilities to private business enterprises; and ceded much prime farmland to foreign corporations, for their sole, private, economic exploitation.[10]

- Military government

The régimes of Manuel José Estrada Cabrera (1898–1920) and of General Jorge Ubico

(1931–1944) opened the land and the economy of Guatemala to

unrestricted foreign investment. Moreover, General Ubico especially

granted favors — political and financial — to the United Fruit Company (UFC) whose investment capital bought controlling shares of the capital stock that financed the construction of the railroads, the telegraph, and the electric utility,

the economic infrastructure of the Republic of Guatemala. In his

politico-economic favoritism, President Ubico ceded physical control of

much of Guatemala’s best agricultural land, and de facto control of Puerto Barrios,

the Caribbean Sea port that grants Guatemala access to the Atlantic

Ocean, in exchange for building the (road, rail, and telegraph)

infrastructure; resultantly, in labor-and-management relations, the

Guatemalan government often was politically subservient to foreign

business interests, especially those of the United Fruit Company.

In 1930, the U.S. supported the presidential ascension of General Jorge Ubico (1931–1944), who, under the guise of public efficiency, installed a national “March Towards Civilization”, by which he assumed dictatorial powers, and established a politically repressive régime that featured internal espionage (agents provocateur, spies, informants), arbitrary arrest, torture, and execution of political opponents. Personally, General Ubico was a wealthy aristocrat, with an income of $215,000 per annum. Politically, he was anti-communist, and so usually protected the financial and economic interests of the Guatemalan élites, the landed gentry and the urban bourgeoisie, especially in matters of land ownership and labor relations, against the legal complaints of the working class, trade unions, and the peasantry. To that effect, General Ubico installed debt slavery, a feudal labor management system of forced labor, the laws of which permitted landlords to discipline their workforces with capital punishment, when necessary, for the efficient functioning of the business enterprise.[11][12][13][14][15] As a self-identified fascist, Gen. Ubico openly admired his dictator contemporaries the Italian Benito Mussolini, the Spanish Francisco Franco, and the German Adolf Hitler; racially, he disdained the indigenous Maya

population of Guatemala, whom he described as “animal-like”, and who

needed to be “civilized” with mandatory military training; that it would

be like “domesticating donkeys”.[16][17][18][19][20] As a plutocrat, he ceded thousands of hectares of prime agricultural land to the United Fruit Company (UFC), and exempted them from paying taxes.

Strategically, as President of Guatemala, General Ubico allowed the

establishment of U.S. military bases in Guatemala, thus submitting

Guatemala to U.S. hegemony.[11][12][13][14][15]

- Civil government

The thirteen-year dictatorship of General Jorge Ubico ended with the October Revolution of 1944,

which initiated “Ten Years of Spring” in the national politics of

Guatemala. The free election that followed installed a philosophically

conservative university professor Juan José Arévalo Bermejo, as the President of Guatemala (1945–1951); and a new political constitution allowed the legal possibility of expropriating

unused farmland for the benefit of the Guatemalan peasant majority. Yet

the liberal social and economic policies derived from the new political

constitution and the “spiritual socialism” philosophy of President

Arévalo Bermejo, made the landed gentry and the urban bourgeoisie first distrust, and then accuse the President of Guatemala of supporting communism,

a serious personal and political accusation during the Cold War, of

which the U.S. took serious note. Furthermore, in 1947, the Arévalo

Government promulgated a liberal labor law that favored the rights of

workers, and implicitly attacked the exploitive business practices of

the United Fruit Company (UFC).

Hence, because of the business complaints of the UFC, the U.S.

embassy in Guatemala City sent alarmist political intelligence to

Washington, D.C. — that Guatemalan President Arévalo Bermejo allowed

political rights to Guatemalan communists. Moreover, in keeping with his

spiritual-socialism philosophy, President Arévalo Bermejo supported the

Caribbean Legion, a group of reformist Latin American military officers and intellectuals who plotted the deposition of right-wing dictatorships in Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and Venezuela;

the CIA described the Caribbean Legion as a politically destabilizing

force, dangerous to U.S. geopolitical interests in the Western

Hemisphere.[21] As a participant in the October Revolution of 1944, the Army Captain Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, facilitated the transition from military dictatorship to representative democracy, when he, and a comrade officer, Major Arana, forsook the Presidency of Guatemala

for constitutional government, which earned them and the Army much

popular respect as patriots. Later, in 1950, the presidential candidate

Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán received 65 per cent of the votes. In

post-dictatorship Guatemala, the Political Constitution of Guatemala

allowed only a six-year term, and forbade presidential re-election.

- Land reform

For the social and economic reformation of the Republic of Guatemala, President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán advocated the unionization of the working class and land reform

for the landless-peasant majority of the population. In 1951, to

equitably redistribute the arable lands, the President worked with the

Communist Partido Guatemalteco del Trabajo

(PGT, Guatemalan Labor Party) to jointly compose, implement, and

establish a realistic land-reform program that would remedy the

inequitable distribution of farmland in Guatemala, which dated from the Spanish Conquest, the Colonial period, and the military dictatorships. In 1945, the Guatemalan bourgeoisie

— approximately 2.2 per cent of the national population — owned 70 per

cent of the arable land of Guatemala, yet economically exploited only 12

per cent of that land; meanwhile, the remaining 97.8 per cent of the

Guatemalan population were landless laborers.[8] In 1952, the Árbenz Government promulgated land reform and redistribution with Decree 900; the landless-peasant majority welcomed the progressive changes to the Guatemalan Old Order of the dictatorships of Manuel José Estrada Cabrera and Jorge Ubico.

Because of the liberal changes to the economy of Guatemala, the

land-owning upper classes, and political factions in the military,

publicly accused President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán of being unduly

influenced by the four-man Communist minority in the fifty-six-member

Guatemalan national senate; nonetheless, the resultant political

tensions provoked civil unrest throughout the country, and threatened

the Guatemalan business interests of the United Fruit Company.[22]

In March 1953, the Árbenz Government expropriated unused UFC farmlands,

for which the company was to be paid US$600,000 — as determined by the

UFC’s public tax-declaration of the worth of the unused farmland. In

October 1953 and in February 1954, the Guatemalan Government further

expropriated 60,702.846 hectares

(150,000 acres) of unused farmland from the UFC; to that date, the

total area of the farmlands expropriated from the United Fruit Company

was approximately 161,874.26 hectares (400,000 acres). Consequently, the

UFC complained to and sought financial redress through the U.S.

Government; and, in 1954, the U.S. State Department demanded that the

Árbenz Government pay $15,854,849 to the United Fruit Company, in

payment of the true value of its farmland in the Pacific Ocean coast of

Guatemala. In turn, the Árbenz Government rejected the usurious demand

for over-payment, as a violation of the national sovereignty of the

Republic of Guatemala.[23]

In 1953, as the land expropriations occurred, the United Fruit

Company asked the Eisenhower Administration to confront the Árbenz

Government, and reverse Decree 900. To involve the reticent President Eisenhower, the UFC employed the public relations-and-advertising expert Edward L. Bernays

to create, organise, and direct a psychologically inflammatory,

anti-Communist disinformation campaign (print, radio, film, television)

against the liberal Guatemalan government of President Jacobo Árbenz

Guzmán. The public-opinion pressure compelled President Eisenhower to

become involved in the business–government quarrel of the UFC, lest he

appear to be “soft on Communism” in Guatemala, a great political danger

during the McCarthy Era.[24] Hence, the U.S. State Department, reduced economic aid

to and commercial trade with Guatemala, which harmed the national

Guatemalan economy, because 85 per cent of exports were sold to the

United States, and 85 per cent imports were bought from the United

States. The economic sabotage of Guatemala was secret, because economic warfare

violated the Latin American non-intervention agreement to which the

United States was a signatory party; public knowledge that the U.S. was

violating the non-intervention agreement would prompt other Latin

American countries to aid Guatemala in surviving the economic warfare.[25]

- Counter-revolution

In 1951, the initial plan to overthrow the liberal Árbenz Government, Operation PBFORTUNE,

was prepared before the expropriation of the Guatemalan farmlands of

the United Fruit Company. Ideologically, “in the Agency’s view, Árbenz’s

toleration for known Communists made him, at best, a ‘fellow traveler’ and, at worst, a Communist, himself. The social unrest that accompanied the passage and implementation of the Agrarian Reform Law supplied Guatemalan and U.S. critics with confirmation that a Communist beachhead had been established in the Americas. Agrarian reform was not the issue — Communism was”.[26]

Hence, to facilitate unencumbered authorization of the paramilitary

invasion, the propaganda campaign of Operation PBSUCCESS exaggerated

U.S. Government fears of a Communist Guatemala under the Árbenz

Government, and installed Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas as President of

Guatemala. Afterwards, to justify American intervention to the internal

politics of the Republic of Guatemala, the CIA launched Operation

PBHISTORY, which unsuccessfully sought Guatemalan government documents

that proved that, under the Árbenz Government, Guatemala was a puppet state of the U.S.S.R. in the Western Hemisphere.

- CIA operational names

The name of the 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état, Operation PBSUCCESS, is a cryptonym composed of a digraph (two-character prefix), which designates the functional, geographic area where the mission is effected. In the name Operation PBSUCCESS, the prefix PB denotes “Republic of Guatemala”, and the words SUCCESS and FORTUNE,

respectively indicated the optimism and confidence of the CIA planners.

Moreover, in CIA cryptonymic practice, the PBSUCCESS and PBFORTUNE

operational names were unusual, because most operational names either

were arbitrary-word or misleading titles, meant to hide the true temper

of paramilitary actions. (see: CIA cryptonyms)

Operation PBFORTUNE

Main article: Operation PBFORTUNE

- Deposition of a “Communist puppet-state”

As early as 1951, before the Agrarian Reform Law had been promulgated in June 1952, the CIA’s geopolitical fear of a Communist, political conquest of Guatemala, sponsored by the U.S.S.R, prompted the deposition of the liberal Árbenz Government. Ideologically, to the CIA, President Árbenz’s toleration for “known Communists” made him, at best, a “fellow traveller”, a communist sympathizer, and, at worst, a Communist, himself.[21]

The most feasible way of overthrowing President Árbenz was secret

support (financial, logistical, military) of his ideological opponents —

exiled Guatemalan rebel-groups, and right-wing and anti-Communist politicians in Guatemala. To that effect, CIA Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Walter Bedell Smith

despatched a secret agent to Guatemala City, to find and investigate

potential candidates and organizations who would aid a U.S. coup d’état against the liberal Árbenz Government — which included Communists from the Guatemalan Labor Party.

In that time, the exiled political opponents of the Árbenz Government

were ideologically divided, and thus impotent to overthrow the elected

government of Guatemala. In the event, the CIA case officer reported to

DCI Bedell Smith that there existed no reliable politician or military

officer available to betray the national sovereignty of the Republic of Guatemala.

Fortuitously for the CIA, that failed scouting trip coincided with the first U.S. state visit of Anastasio Somoza García, the President of Nicaragua (1937–47, 1950–56), who informed the Truman Administration

(1945–53) of the existence of a small, Guatemalan rebel-group commanded

by Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas; in exchange for CIA aid and support,

the Nicaraguan dictator then offered to help the U.S. depose the

Guatemalan president. Somoza further explained that the coup d’état also would be financially supported by President Rafael Trujillo,

dictator of the Dominican Republic, in exchange for the CIA’s

assassination of Dominican opponents exiled in Guatemala. In June 1951,

DCI Bedell Smith ordered CIA acceptance of the Somoza and Trujillo

offers, and the establishment of connections with Col. Castillo Armas

and his anti-Communist supporters. The CIA requested from Col. Castillo

Armas a plan for the invasion of Guatemala; the Colonel planned to

launch simultaneous attacks from Mexico, El Salvador, and Honduras,

which would be co-ordinated with simultaneous anti-Communist

insurrections throughout Guatemala. To effect the invasion, the Colonel

requested money and matériel, yet nonetheless told the CIA that his army of liberation, El ejército de liberación, would invade Guatemala, with or without U.S. support.

In September 1951, the U.S. State Department approved Operation PBFORTUNE, the paramilitary coup d’état

against the Árbenz Government. Nevertheless, shortly afterwards,

shipment of the Soviet weapons for the Castillo Armas army of liberation

was postponed — because, in conversation with other Central American heads of state,

the indiscreet Nicaraguan President Somoza García had openly spoken

about the CIA's planned deposition of President Árbenz. Public knowledge

of the betrayed secret-intervention would provoke diplomatic problems

for the U.S. — a signatory party to the Rio Pact (1947), a Latin American non-intervention treaty derived from the Good Neighbor Policy of the FDR Administration

(1933–45). For which reason, President Somoza’s public boasting, the

State Department and the CIA deactivated Operation PBFORTUNE until its

reactivation became politically feasible; the liberation army matériel were stored, and the military caudillo

services of Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas were retained, for

three-thousand weekly dollars, until required to be President of

Guatemala.

Operation PBSUCCESS

- The coup d’état

In the post–War United States, the departure of the cautious Truman Administration (1945–53) and the arrival of the adventurous Eisenhower Administration (1953–61), abetted by the right-ward Cold War national political climate, rekindled Presidential interest in covert operations,

which reanimated CIA advocacy of a paramilitary invasion of Guatemala

to depose President Árbenz Guzmán and his government. Strategically,

President Eisenhower favored the secret warfare of covert operations, as

cost-effective means for combating the world-wide hegemony of the U.S.S.R. In that context, the U.S. National Security Council revived the Guatemalan coup d’état after reviewing the malleability of anti–Árbenz politics, and because of the successful Iranian coup d’état against the elected Government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, in 1953.[27]

To initiate Operation PBSUCCESS, the CIA selected the Guatemalan

politico-military leader who would succeed Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán as

President of Guatemala, and establish a pro–American Guatemalan

government. The three exile candidates were: (i) the coffee planter Juan

Córdova Cerna, formerly of the Cabinet of Advisors to the reformist

President Juan José Arévalo Bermejo (1945–51), and who also was a business consultant to the United Fruit Company, which he aided in repressing a workers’ revolt. (ii) General Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, a department governor under General Ubico; he was pro–Nazi until 1943, when he changed fascist allegiance for democratic allegiance, and became pro–U.S.; as such, he mediated the overthrowing of General Juan Federico Ponce Vaides, one of the triumvirate junta who succeeded the deposed dictator, General Jorge Ubico. (iii) Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas,

a contemporary of Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán at the Guatemalan national

military academy. As the most politically amenable white-horse caudillo, the CIA appointed Col. Castillo Armas as leader of the Guatemalan army of liberation, the core of Operation PBSUCCESS.

Because of the continual bureaucratic

postponements of the paramilitary invasion, the CIA worried that their

Guatemalan army of liberation, or any other Guatemalan armed

rebel-group, might prove over-eager and prematurely launch a coup d’ état. The worry proved true on 29 March 1953, when a futile raid against the Army garrison at Salamá, in central Guatemala, was launched by a rebel group associated with Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas

— one of three men whom CIA considered installing as President of

Guatemala. Besides the defeat and the jailing of the rebels, the failed

invasion provoked the political response most feared by CIA — the Árbenz

Government repressed and jailed the anti-Communists connected with the exile rebels, and all other potentially treasonous

right-wing politicians. Most Guatemalans supported the President’s

repression, because the exile rebels and the domestic politicians sought

to subvert

the constitutionally-elected government of Guatemala with the aid of a

foreign power, the United States. The jailing of the CIA’s Guatemalan

secret agents rendered them operationally ineffective; thus, the CIA

then relied upon the ideologically-fragmented Guatemalan exile-groups,

and their anti-democratic allies in Guatemala, to realize the coup d’état against President Árbenz Guzmán.[28]

In December 1953, the CIA established the operational headquarters of

the Guatemalan army of liberation in suburban Florida; then recruited

aeroplane pilots and mercenary soldiers, supervised their military

training, established the radio station La Voz de la Liberación (The Voice of Liberation) to broadcast disinformation and propaganda; and arranged for increased diplomatic pressure upon Guatemala to reverse the Agrarian Reform Law of Decree 900 — especially as it applied to the United Fruit Company. Moreover, despite being unable to halt the exportation of Guatemalan coffee,

the U.S. ceased selling arms to Guatemala in 1951; in 1953, the State

Department aggravated the American arms embargo by thwarting Árbenz

Government arms purchases from Canada, Germany, and Rhodesia. Faced with

dwindling supplies of matériel, and having noted the unusually

armed borders of Honduras, El Salvador, and other neighbor countries,

President Árbenz Guzmán acted upon the intelligence indications of an

imminent paramilitary invasion of Guatemala — confirmed by a defector from Operation PBSUCCESS — and bought matériel in the Eastern Hemisphere.[29] The Árbenz Government bought surplus Wehrmacht matériel from the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, a Communist satellite country of the U.S.S.R. The weapons were delivered to Guatemala at the Atlantic Ocean port of Puerto Barrios, by the Swedish freight ship MS Alfhem, which sailed from port Szczecin, in the People’s Republic of Poland, a Communist, satellite country of the U.S.S.R. The U.S. State Department and the CIA tried to halt the arms-laden Ms Alfhem en route to Guatemala; in one instance, the CIA seized the freight ship Wulfsbrook, having mistaken it for the MS Alfhem.

Nonetheless, despite the intelligence failure having allowed “Communist

Czech arms” to reach Guatemala, in the American press, to the American

public, the CIA misrepresented the arms purchase as a Soviet provocation

in “America’s Back yard”.

- The national defense of Guatemala

The Árbenz Government originally meant to repel the invasion by arming the military-age populace, the workers’ militia, and the Guatemalan Army;

yet, public knowledge of the secret, cash-and-carry arms-purchase

compelled the President to supply arms only to the Army; which the

Guatemalan senate perceived as a political rift, between the President

and the Military Establishment. Although the purchase of surplus Wehrmacht

arms had been from Czechoslovakia, not from the U.S.S.R., the Operation

PBSUCCESS propaganda misrepresented the business transaction as proof

of direct Soviet interference in the Western Hemisphere — a geopolitical

impingement upon the U.S. hegemony established in the Monroe Doctrine (1823). To the American public, the U.S. press reported that the Republic of Guatemala was suffering an externally instigated, vanguard party

Communist revolution, like those occurred in the Eastern European

countries that border the U.S.S.R. The disinformation and propaganda

planted in the U.S. news media, about the Guatemalan–Czech arms purchase

and the arrival of the weapons to Guatemala, provoked much popular

support for American military intervention. The fabricated domestic

support allowed the Eisenhower Administration to increase the intensity

of its open and secret wars against the Republic of Guatemala.

On 20 May 1954, the U.S. Navy began air and sea patrols of Guatemala,

under the pretexts of intercepting secret shipments of weapons, and the

protection of Honduras from Guatemalan aggression and invasion.[30]

On 24 May 1954, the U.S. Navy launched Operation HARDROCK BAKER, a

blockade of Guatemala, wherein submarines and surface ships intercepted

and boarded every ship in Guatemalan waters, and forcefully searched it

for Guatemala-bound weapons that might support the “Communist Árbenz

Government”. The blockade included British and French ships, which

violations of maritime national sovereignty neither Britain nor France

protested, because they wished to avoid U.S. intervention to their

colonial matters in the Middle East; additionally, the blockade

facilitated further psychological warfare against the Guatemalan Army.

To disseminate propaganda, the military aeroplanes of Col. Castillo

Armas flew over Guatemala City, dropping leaflets that exhorted the

people of Guatemala to: Struggle against Communist atheism, Communist

intervention, Communist oppression . . . Struggle with your patriotic

brothers! Struggle with Castillo Armas! The messages were meant to

turn the Guatemalan Army against President Árbenz Guzmán, personally,

and against Communism, as economic policy. Moreover, the rebel

aeroplanes flying over the cities were perceived as practicing bombing

runs, which Guatemalans perceived as indicative of an imminent invasion.

On 7 June 1954, a contingency evacuation-force of five amphibious

assault ships, a U.S. Marines helicopter-assault Battalion Landing Team,

and an anti-submarine aircraft carrier, were despatched to blockade the

Guatemalan sea lanes.

- Propaganda and disinformation

The Guatemalan coup d’état much depended upon psychological warfare,

because the 480-soldier Guatemalan army of liberation was over-matched

by the Guatemalan Army; thus, deception by feint was most important.[31] The CIA used propaganda in the forms of political rumour, air-dropped pamphlets, poster campaigns, and radio

(the mass communications medium that successfully deceived most of the

Iranian populace to accept the foreign deposition of the elected

government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh). In third-world

Guatemala, few people owned radio receivers; nonetheless, Guatemalans

considered the medium of radio as an authoritative source of

information. As directed by CIA case officers, from Florida, right-wing

student groups successfully conducted internal propaganda, such as

publishing El combate (The Combat),a weekly political pamphlet,

covering walls and buses with the number "32" — referring to Article 32

of the Guatemalan Constitution, which forbade foreign-financed political

parties; the propaganda claims received much attention from the local

and the national press. Other psychological warfare techniques included

character assassination, with signs that read: A Communist Lives Here

affixed to the houses of Árbenz supporters; and the month-long daily

delivery of false death-notices to President Árbenz Guzmán, his Cabinet

of Advisors, and known Communists.

In due course, the disinformation-propaganda campaign provoked the

Árbenz Government to politically repress the Guatemalan right wing, by

arresting rightist students, limiting freedom of assembly, and

intimidating newspapers. Furthermore, the CIA expected gossip

(word-of-mouth) to assist in propagating anti-Communist claims against

the elected Árbenz Government. From Florida, The Voice of Liberation

radio station, which claimed to be broadcasting from the Guatemalan

jungle, transmitted music, “news”, disinformation, and anti–Árbenz

propaganda. Most of the radio programming was for the general populace,

yet some propaganda specifically was a seditious call-to-arms meant to appeal to the right-wing men of action in the officer corps of the Guatemalan military, whose treasonous complicity was essential to the success of the deposition

of the elected Árbenz Government. The collaboration of the Guatemalan

army (ca. 5,000 soldiers) was most important, because, as a professional

military force, they could readily out-fight and defeat the CIA mercenary

army of liberation of Col. Carlos Castillo Armas. Nonetheless, because

of the socio-political and military realities, the CIA knew that the

Castillo Armas army of liberation could not conquer Guatemala with 480

mercenary soldiers. Hence, the importance of propaganda, of the

co-optation of the Guatemalan military-officer corps to the usurpation

of Guatemalan representative democracy, by overthrowing the “Communist government” of President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán.

- The CIA invasion of Guatemala

At 8:00 p.m. on 18 June 1954, the Ejército de liberación of

Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, invaded Guatemala; in four groups, the

480 soldiers entered the country at five key points of the

Honduras–Guatemala border and of the Guatemala–El Salvador border.

Multiple attacks, along a wide front, were meant to give impress the

populace that the Republic of Guatemala was being invaded by a military

force superior to and of greater size than the Guatemalan Army. The

four-group dispersal of the CIA mercenary army meant to minimize the

possibility of a decisive rout, and of the coup d’état being

thwarted, with a single, unfavorable battle. Ten saboteurs, tasked to

destroy key bridges and telegraph communications, which would hinder the

national defense of Guatemala, preceded the main attack force of the

liberationist army. Nonetheless, the CIA ordered Col. Castillo Armas to

avoid fighting the Guatemalan Army, lest the defenders co-ordinate

tactics, and either kill or capture the CIA invaders. As psychological

warfare, the course of the 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état invasion

was meant to provoke popular panic, by giving the populace the

impression of strategically insurmountable odds against successfully

defending Guatemala, which, the CIA believed, would compel the national

populace and the Guatemalan Army to side with, rather than repel and

defeat, the invaders. Throughout the invasion, The Voice of Liberation

broadcast false news of a popular, right-wing counter-revolution

occurring; of great military forces being welcomed and joined by the

local populace, to overthrow the Communist Árbenz Government.

Almost immediately, the forces of Col. Castillo Armas met with

decisive failure. Invading on foot and hampered by heavy equipment, in

some cases, it was days before the invaders reached their strategic

objectives. The weakened psychological impact of the initial invasion

allowed local Guatemalans to understand that they were not endangered.

One of the first liberationist units to reach their strategic objective

was a group of 122 mercenaries tasked to capture the city of Zacapa;

despite their superior number, they were defeated by a 30-man platoon

of the Guatemalan Army; only 28 mercenaries survived the battle.

Elsewhere, in northern Guatemala, a 170-mercenary unit was defeated when

they attempted to capture the guarded port city of Puerto Barrios.

When the chief of police saw the mercenary invaders, he armed the local

longshoremen and assigned them defensive positions. Hours later, after

the defensive battle, most of the 170 mercenaries had been killed or

captured; some escaped, and fled to Honduras. Within three days, the

Guatemalan Army had rendered combat-ineffective two of the four units of

the army of liberation of Col. Castillo Armas. To recover the

initiative, the Colonel ordered an air attack upon Guatemala City; the

desultory attack upon the national capital failed — a slow aeroplane

only managed to bomb a small oil tank, which fire the defenders quickly

suffocated.[32]

Despite the tactical and strategic failures of the Guatemalan army of

liberation, President Árbenz ordered his military commander to allow

the forces of Col. Castillo Armas to advance deep into the territory of

Guatemala. Although the invaders were not a significant military threat,

the President and the military commander did fear U.S. military

intervention if the Guatemalan military decisively defeated the CIA

invasion. Such geopolitical political fear soon panicked the Guatemalan

officer corps; no tactical commander wished to provoke the intervention

of the U.S. military forces that had blockaded Guatemala. The presence

of the U.S. Navy amphibious assault force prompted rumours that the U.S.

Marines already had established a beachhead in Honduras, en route to

invading Guatemala. President Árbenz Guzmán feared that the military

officers would be intimidated to side with Col. Castillo Armas; days

later, the Army garrison at Chiquimula surrendered to the liberacionista

army of Col. Castillo Armas. After such a revolt by the Guatemalan

Army, the President explained crisis of confidence to his Cabinet of

Advisors, and on 27 June 1954, Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán resigned the

Presidency of Guatemala, for exile in Mexico.

U.S. news media reportage

Edward Bernays, known as the “Father of Public Relations”, had among his clients the Eisenhower Administration and the United Fruit Company

whilst he engineered popular consent for the CIA’s overthrowing of a

capitalist democracy in Guatemala in 1954. Bernays’s propaganda

operation used the North American press to frighten the American public

to believe that President Árbenz Guzmán was a political puppet

of the U.S.S.R., and that Guatemala had become a Soviet beachhead in

the Western Hemisphere. The principal American news media misinformed

the American public that the Árbenz Government had been overthrown by

the CIA, and, instead, misrepresented it as a liberation from Communist

tyranny by native Guatemalan freedom fighters restoring democracy to

their country.[33]

The CIA did little to hide their paramilitary involvement from the

American public, “The figleaf was very transparent, threadbare”, said a

CIA official.[34] In the New York Times,

Milton Brackersan misinformed his readers: “There is no evidence that

the United States provided material aid or guidance” to the

anti-Communist freedom fighters.[35] The New York Times

explained that “Castillo Armas had the moral support of the United

States; the Árbenz régime had the support of the Soviet Union.”[36] The New Republic

said that “It was just our luck that Castillo Armas did come by some

second-hand lethal weapons, from Heaven knows where.” Newsweek said,

“The United States, aside from whatever gumshoe work the Central

Intelligence Agency may or may not have been busy with, had kept hands

strictly off.” The Eisenhower Administration could have expedited the

overthrowing of President Árbenz Guzmán, “overnight, if necessary: by

halting coffee purchases, shutting off oil and gasoline from Guatemala,

or, as a last resort, by promoting a border incident, and sending

Marines to help the Hondurans. Instead it followed the letter of the

law.” President Árbenz Guzmán was overthrown “in the best possible way:

by the Guatemalans.”[37] The New York Times celebrated the Guatemalan coup d’état by celebrating it as “the first successful anti-Communist revolt since the last war.”[38]

About how co-operative the American press was in engineering public

consent for the CIA’s overthrowing of Guatemalan democracy, the UFC

public-relations man, Thomas P. McCann, said: “For about eight years

[1953–1960] a great deal of the news of Central America, which appeared

in the North American press, was supplied, edited, and sometimes made by

United Fruit’s public relations department in New York. It is difficult

to make a convincing case for manipulation of the press when the

victims proved so eager for the experience.”[39]

Operation PBHISTORY

After the PBSUCCESS coup d’état, the CIA launched Operation PBHISTORY,

a document analysis team to Guatemala to collect and analyze Árbenz

Government and Guatemalan Labour Party documents that would be evidence

to support the geopolitical belief of the CIA that, under the presidency of Colonel Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, the Republic of Guatemala was a Communist puppet state in the Western Hemisphere hegemony of the Soviet Union.

CIA intelligence analyses, of some 150,000 pages of Guatemalan

Government and communist party documents, found no substantiation of the

key geopolitical premise that justified the secret U.S. paramilitary

invasion of Guatemala, and the deposition of the elected Árbenz Government.[32] The socialism

practiced by the Árbenz Government was unrelated to the geopolitics of

the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, some U.S. businessmen and military

officers believed that the nationalism of President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán was a Communist threat to the business interests of American multinational corporations, and advocated and supported the coup d’état against his government, despite the Guatemalan majority’s support and attachment to the original political principles of the "October Revolution" of 1944.

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the Guatemalan coup d’état, which deposed Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán by compelled resignation of the Presidency of Guatemala, the CIA-installed usurper government had difficulty persuading the officer corps of the Guatemalan Army to abandon their Constitutional allegiance to the head-of-state President, and become the Guatemalan Army commanded by Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas.

In the event, most of the officer corps abandoned the elected President

of Guatemala, because, as political conservatives, they disliked the

Agrarian Reform Law (Decree 900)

and its socio-economic changes, yet neither did they prefer the régime

of Col. Castillo Armas. The popular response of the Guatemalan nation,

to having had their elected government usurped by right-wing counter-revolution, varied by social class. The upper-class landowners welcomed the end of the Decree 900 agrarian reform, and expected the U.S. to reinstate their monopoly ownership of expropriated agricultural lands. Likewise, the native Maya

had political opinions about the counter-revolution, those who

benefitted from Decree 900 were unhappy, whilst those who lost lands to

Decree 900 were happy, especially those Maya whose autonomous

communities had lost political power to the Árbenz Government; other

Maya Guatemalans favored President Árbenz Guzmán, like most Guatemalans,

and understood the socio-political importance of the Decree 900

Agrarian Reform Law. In the cities of Antigua Guatemala, San Martín Jilotepeque, and San Juan Sacatepéquez

pro–Árbenz armed groups combated the Castillo Armas Government, because

of the forced presidential resignation, and because they had benefited

from the Decree 900 land reform. In the event, the U.S.-installed

military government of Colonel Carlos Castillo proved reactionary,

and reversed the land-reform expropriations, returned the farmlands to

private owners, for which reason some Guatemalan farmers burned their

crops as economic protest.

- Military government reinstated

In the eleven days after the resignation of President Árbenz Guzmán, five successive military junta governments occupied the Guatemalan presidential palace; each junta

was successively more amenable to the political demands of the U.S.,

after which, Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas assumed the Presidency of

Guatemala. As the Guatemalan head-of-state, Col. Castillo Armas proved an inept administrator, installed a corrupt bureaucracy, and vigorously repressed the civil warfare that resulted from the Guatemalan coup d’état

in 1954; the previous occurrence of violent repression was a decade

earlier, before the democratic October Revolution of 1944. International

opinion reviled the Guatemalan coup d’état, the French and British press, Le Monde and The Times, attacked the United States’ “modern form of economic colonialism”. In Latin America,

public and official opinions provoked much political criticism of the

U.S. deposition of an elected Latin American government, and Guatemala

became symbolic of armed resistance to the U.S. hegemony of Latin America. The Secretary General of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld

(1953–61), said that the paramilitary invasion by which the U.S.

deposed the elected Guatemalan government violated the human-rights

stipulations of the UN Charter; moreover, the usually pro–U.S. newspapers of West Germany, condemned the Guatemalan coup d’état. Historically, the Director of the Mexico Project of National Security Archives, Kate Doyle, said that the 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état was the definitive deathblow to democracy in the Republic of Guatemala.

- Civil War

The Guatemalan Civil War ran from 1960 to 1996. It was mostly fought between the Government of Guatemala and insurgents. The Historical Clarification Commission reports that the influence of the Guatemalan military

over the government occurred in different stages during the years of

the civil war. Because it dominated the executive branch of the civil

government during the 1960s and the 1970s, the military infiltrated

every institution of Guatemalan national government and civil society.

Subsequently, during the 1980s, the Guatemalan military assumed almost

absolute government power for five years, having successfully

infiltrated and eliminated enemies in every socio-political institution

of the nation, including the political, social, and ideological classes.

In the final stage of the civil war, the military developed a parallel,

semi-visible, low profile, but high-impact, control of Guatemala's

national life.[40] In the latter stages of the thirty-six-year Guatemalan Civil War (1960–1996), the CIA reduced the incidence and number of the violations of the human rights of Guatemalans; and, in 1983, thwarted a palace coup d’ état, which allowed the eventual restoration of participatory democracy and civil government; the resultant national election was won by Democrácia Cristiana, the Christian Democracy party, whereby Marco Vinicio Cerezo Arévalo became President of the Republic of Guatemala (1986–91).[41] The casualties of the war are estimated at between 140,000 and 200,000 dead and missing[42][43][44][45]

In retrospect, Richard M. Bissell, Jr., a Special Assistant to the CIA Director, denied that the 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état

resulted from the conflation of private, multinational, business

interests and U.S. Government foreign policy; he said that there “is

absolutely no reason to believe” that the Eisenhower Administration’s (1953–61) desire to help the United Fruit Company had “any significant role” in deciding to depose the elected Árbenz Government of Guatemala.[1][46] Nonetheless, CIA case officer Howard Hunt, an agent of the Guatemalan coup d’ état, said that the political influence of the United Fruit Company

upon the Eisenhower Administration was instrumental in the CIA’s

overthrowing the progressive Guatemalan President, Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán,

in order to protect the national security of the U.S., and the international security of the Western Hemisphere against the hegemony of the U.S.S.R.[47] In 2003, the U.S. State Department confirmed that the 1954 Guatemalan coup d’ état, resulted from the CIA’s mistaken geopolitical perceptions that the civil unrest consequent to the nationalization

of foreign-owned farmlands was the work of the Guatemalan Labor Party,

and its Communist influence upon President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán.[26]

See also

- Banana republic

- Church Committee

- Covert U.S. regime change actions

- Guatemalan Civil War

- History of Guatemala

- National Committee of Defense Against Communism

- Operation Kufire

- Operation Kugown

- Operation PBFORTUNE

- Operation PBHISTORY

- Operation WASHTUB

- Plausible deniability

- Timeline of United States military operations

Further reading

- Chapman, Peter (2008). Bananas!: How The United Fruit Company Shaped the World. Canongate U.S.. ISBN 1-84195-881-6.

- Cullather, Nick (1999). Secret History: The CIA's classified account of its operations in Guatemala, 1952-1954. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3311-2.

- Gleijeses, Piero (1992). Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944-1954. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02556-8.

- Immerman, R. H., The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention, University of Texas Press: Austin, 1982.

- Handy, Jim (1994). Revolution in the Countryside: Rural Conflict and Agrarian Reform in Guatemala 1944-54. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4438-1.

- Kinzer, Stephen and Schlesinger, Stephen. 1999. Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. Cambridge Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- La Feber, Walter (1993). Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America. Norton Press. ISBN 0-393-03434-8.

- Asturias, Miguel Ángel, Week-end in Guatemala (1956) is a fictional account of the 1954 Guatemalan coup d’ état.

- Vidal, Gore, Dark Green, Bright Red (1950, 1968), a novel about the people involved in a banana republic coup d’état.

References

- ^ a b Crisis in Central America on PBS Frontline, The New York Times April 9, 1985, p. 16.

- ^ "Images and Intervention: U.S. Policies in Latin America" by Martha L. Cottam, University of Pittsburgh Press, 15 April 1994

- ^ "The Hovering Giant: U.S. Responses to Revolutionary Change in Latin America" By Cole Blasier, Jan 15, 1985

- ^ "Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944-1954" By Piero Gleijeses, 1992, P. 365

- ^ "Interpreting the 1954 U.S. Intervention in Guatemala: Realist, Revisionist, and Postrevisionist Perspectives" Stephen M. Streeter, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario

- ^ Cullather, Nick (1999). Secret History: The CIA's classified account of its operations in Guatemala, 1952-1954. Stanford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-8047-3311-2.

- ^ http://thoughtcontrol.us/same-as-it-ever-was/2010/07/guatemala-the-ufc-and-the-dulles-brothers/

- ^ a b Stanley, Diane (1994). For the Record: United Fruit Company's Sixty-Six Years in Guatemala. Centro Impresor Piedra Santa. p. 179.

- ^ Shea, Maureen E. (2001). Culture and Customs of Guatemala. Culture and Customs of Latin American and the Caribbean Series, Peter Standish (e.) London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30596-X.

- ^ Streeter, 2000: pp. 8-10

- ^ a b Streeter, 2000: pp. 11-12

- ^ a b Immerman, 1983: pp. 34-37

- ^ a b Cullather, 2006: pp. 9-10

- ^ a b Rabe, 1988: p. 43

- ^ a b McCreery, 1994: pp. 316-317

- ^ Shillington, John (2002). Grappling with atrocity: Guatemalan theater in the 1990s. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-8386-3930-6.

- ^ LaFeber, Walter (1993). Inevitable revolutions: the United States in Central America. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-393-30964-5.

- ^ Forster, 2001: p. 81-82

- ^ Friedman, Max Paul (2003). Nazis and good neighbors: the United States campaign against the Germans of Latin America in World War II. Cambridge University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-521-82246-6.

- ^ Krehm, 1999: pp. 44-45

- ^ a b State.gov

- ^ The Good Neighbor: How the United States wrote the History of Central America and the Carribbean (1988), by George Black New York: Pantheon Books p. 98.

- ^ "Guatemala: Square Deal Wanted". Time. May 3, 1954. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ "The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays & The Birth of PR"

- ^ La Feber, Walter (1993). Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America. Norton Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 0-393-03434-8.

- ^ a b Foreign Relations, Guatemala, 1952-1954: Introduction

- ^ Spartacus biography, Schoolnet.co.uk

- ^ Cullather, Nicholas (1994) Operation PBSUCCESS: The United States and Guatemala, 1952–1954. p. 21.

- ^ Cullather, Nicholas (1994) Operation PBSUCCESS: The United States and Guatemala, 1952–1954. p. 36.

- ^ Navy.mil; see entry #29.

- ^ GWU.edu

- ^ a b Cullather, Nick (1999). Secret History: The CIA's classified account of its operations in Guatemala, 1952-1954. Standford University Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-8047-3311-2.

- ^ "THE CENTURY OF THE SELF: The Engineering of Consent" BBC, 2002

- ^ "Shattered Hope: The Guatemalan Revolution and the United States, 1944-1954" By Piero Gleijeses, Jul 28, 1992

- ^ "The Lessons of the Guatemalan Struggle; The overturn meets only part of the problem of communism. We must convince the Latin Americans that our way of life is superior to that of the Communists. Lessons of the Guatemalan Struggle" The New York Times, July 11, 1954

- ^ "THE WORLD; Guatemala: Out Leftists" The New York Times, 1954

- ^ "The Price of Prestige" Newsweek, 1954

- ^ "PEACE PACT IN GUATEMALA" The New York Times, 1954

- ^ "An American company: the tragedy of United Fruit" By Thomas P. McCann, 1976

- ^ "Conclusions: The tragedy of the armed confrontation". Shr.aaas.org. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- ^ Report on the Guatemala Review Intelligence Oversight Board. June 28, 1996.

- ^ Briggs, Billy (2 February 2007). "Billy Briggs on the atrocities of Guatemala's civil war". The Guardian (London).

- ^ "Timeline: Guatemala". BBC News. 9 November 2011.

- ^ CDI: The Center for Defense Information, The Defense Monitor, "The World At War: January 1, 1998".

- ^ War Annual: The World in Conflict [year] War Annual [number].

- ^ US State Department document

- ^ CNN Cold War: Interview with Howard Hunt

External links and further reading

- CIA.gov - CIA's declassified documents on Guatemala CIA Documents Chronicling the 1954 Coup

- US State Dept. site - Foreign Relations, 1952-1954: Guatemala

- American Accountability Project - The Guatemala Genocide

- Guatemala Documentation Project - Provided by the National Security Archive.

- Video: Devils Don't Dream! Analysis of the CIA-sponsored 1954 coup in Guatemala.

- The Guatemala 1954 Documents

- From Árbenz to Zelaya: Chiquita in Latin America - video report by Democracy Now!

- The short film U.S. Warns Russia to Keep Hands off in Guatemala Crisis (1955) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Stephen Schlesinger, Stephen Kinzer, John H. Coatsworth, Richard A. Nuccio (Introduction); Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala

Revised and Expanded edition, David Rockefeller Center for Latin

American Studies (December 30, 2005), trade paperback, 358 pages,

| This 067401930X lacks ISBNs for the books listed in it. Please make it easier to conduct research by listing ISBNs. If the {{Cite book}} or {{citation}} templates are in use, you may add ISBNs automatically, or discuss this issue on the talk page. (April 2012) |

,